Take our continuing professional education course, “Micronutrients and Bone Health.”

Summary

Osteoporosis is a major public health concern in many countries with increasing proportions of people surviving to an age where fractures are common. Osteoporosis is characterized by a degree of bone loss that makes bone fragile and more likely to break. The decline in sex hormone production is a major contributor to osteoporosis in both women and men, although bone loss occurs at a more rapid pace and at a younger age in women due to menopause. Therefore, women are at higher risk of osteoporosis and fracture at a younger age than men.

Condition Overview

Definition

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines osteoporosis as a condition characterized by the deterioration of bone micro-architectural structure and the loss of bone mass, leading to bone fragility and increased susceptibility to fracture (see Diagnosis).

Osteoporosis is primarily a disease affecting older adults. It rarely occurs in younger adults where it is usually associated with conditions like anorexia nervosa or long-term use of glucocorticoids.

Two types of bone loss occur with age:

- Postmenopausal osteoporosis – linked to estrogen withdrawal and is especially significant in the decade that follows menopause in women

- Age-related osteoporosis – associated with old age (>70 years old)

Highlight: Postmenopausal Bone Loss in Women

The rate of bone degradation starts to exceed the rate of bone formation in our thirties, leading to a loss of bone mass over time. At menopause, the dramatic decline in estrogen production by the ovaries initiates a phase of rapid bone loss that lasts for 4-8 years and leads to losses of 5-10% of cortical bone and 20-30% of trabecular bone. This period is followed by a phase with a slower rate of bone loss that lasts for the rest of life and contribute to losses of 20-25% of cortical and trabecular bone.

At menopause, estrogen withdrawal impairs calcium absorption in the intestine and reduces the kidneys’ ability to conserve calcium. As a consequence, calcium intakes fail to balance out the calcium that is lost in feces and urine, and blood calcium begins to fall. This triggers the secretion of the parathyroid hormone that stimulates bone resorption, which releases calcium into the circulation and offsets the negative calcium balance. However, this is done to the detriment of bone integrity: a negative balance of only 50-100 mg/day of calcium over a long period of time is thought to be sufficient to cause osteoporosis.

Highlight: Age-related Osteoporosis

There is little difference in the timing of age-related osteoporosis between genders. Age-related bone loss and increased bone fragility are associated with reductions in physical activity and muscle strength that increase the risk of falling and breaking a bone. Moreover, age-related decline in the levels of steroid hormones — sex hormones and vitamin D — and in the activity of osteoblasts are also thought to contribute to age-related osteoporosis in both men and women.

[Download PDF]

Other Articles

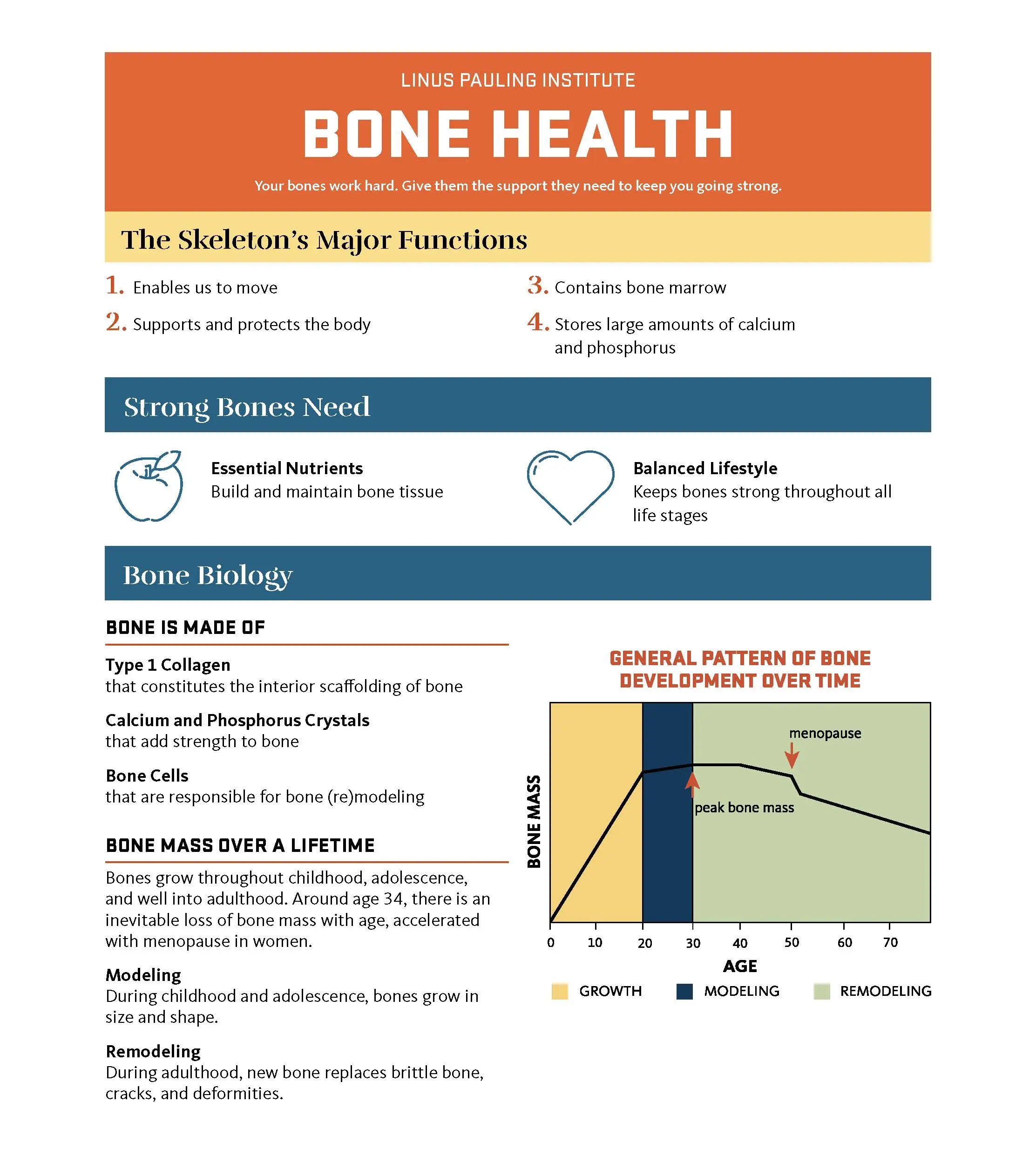

Bone Health In Brief

Bone Health In Depth

Prevalence in the US

Most recent estimates indicate that 43.4 million US adults have low bone mass (see Diagnosis), of which one-third are men and two-thirds are women.

Osteoporosis is also more common in women: an estimated 10.2 million US adults have osteoporosis, of which 8.2 million are women and 2 million are men (see Highlight: Postmenopausal Bone Loss in Women).

Diagnosis

Bone mineral density (BMD) at specific locations of the hip and spine is measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and compared to the standardized mean BMD of a healthy 30-year-old adult. This provides a T-score that is used for diagnostic purposes. Clinically, a T-score of -2.5 standard deviations (SD) or below gives a diagnosis of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men aged ≥50 years (Table 1).

| Condition of Bone Mass | T-score Cutoff |

|---|---|

| Normal bone mass | T-score equal to or above -1 standard deviation (SD) |

| Low bone mass (osteopenia) | T-score between -1 SD and -2.5 SD |

| Osteoporosis | T-score equal to or below -2.5 SD |

Risk of Fracture

The burden of osteoporosis lies primarily in the fractures that arise. Osteoporotic fractures are often precipitated by falls from standing height, although vertebral fractures can occur in the absence of a fall during daily, routine activities. Osteoporosis causes 2 million fractures each year in the US and costs ~20 billion dollars annually. About 70% of osteoporotic fractures affect women. Worldwide, 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men aged >50 years will suffer from a fracture.

The risk of osteoporotic fracture is influenced by bone mass, bone structure (microarchitecture, geometry), and propensity to fall (balance, mobility, muscular strength). The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) is an online tool that helps estimate one’s probability of fracture over the next 10 years, taking BMD measurement and additional risk factors into account (Table 2).

| Risk Factor |

|---|

| Age (between 40 and 90 years) |

| Sex |

| Weight and height |

| Previous osteoporotic fracture |

| Parental history of hip fracture |

| Current tobacco smoking |

| Use of glucocorticoids (>3 months of doses equivalent to 5 mg/day of prednisolone) |

| Confirmed diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis |

| Conditions associated with secondary osteoporosis (type 1 diabetes mellitus, osteogenesis imperfecta, untreated long-standing hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism or premature menopause [<45 years], chronic malnutrition, or malabsorption and chronic liver disease) |

| Alcohol intake: ≥3 units (drinks)/day |

| Low femoral neck BMD |

Fracture-related Morbidity and Mortality

Osteoporotic fractures often lead to a reduced quality of life and premature death. Hip fractures are the most serious of all osteoporotic fractures since 12-20% of women suffering from a hip fracture die during the following 2 years, and 50% of those surviving lose their independence and require long-term nursing care. The risk of death after hip fracture is higher in men than women. Fractures at other sites can also be debilitating. Multiple and/or severe vertebral fractures can lead to loss of height and abnormal bending of the upper and middle back (thoracic spine), reducing lung function and affecting digestion. Vertebral and non-hip, non-vertebral fractures are also associated with premature mortality.

References:

- Pettifor JM, Prentice A, Ward K, Cleaton-Jones P. The skeletal system. Nutrition and Metabolism. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2016:272-311.

- Alswat KA. Gender disparities in osteoporosis. J Clin Med Res. 2017; 9(5):382-387.

For more information:

- See the article, Bone Health In Depth.

- Read the report of the Surgeon General on Bone Health and Osteoporosis (2004).

- Read the press release by the National Osteoporosis Foundation (now the Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation) on low bone mass and osteoporosis prevalence in the US (2014).

- Read the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis (2020).

- Detailed information regarding risk factors can be found in the position statement of the North American Menopause Society on the management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women (2010).

- Visit the website of the International Osteoporosis Foundation.

Nutrition Research

Protein-energy Malnutrition (PEM)

What it is

General

- PEM is caused by deficiencies in macronutrients. Severe forms are known as marasmus (due to severe restrictions in all sources of energy intake) and kwashiorkor (due to severe restrictions in dietary protein).

- PEM is most common in developing nations, the elderly, hospitalized individuals, and those with chronic diseases that interfere with nutrient absorption and utilization. In Western countries, marasmus-type PEM is usually observed in elderly people in the community or in long-term care, whereas low-albumin PEM is found in hospitalized patients.

Bone-specific

- In older adults, PEM may compromise many aspects of health, leading to falls and fracture.

What we know

- Higher protein intakes are associated with greater bone mass density and lower risk of fracture.

- Higher protein intakes are likely to be protective unless calcium intakes are inadequate, in which case higher protein intakes may be harmful.

- Protein supplementation after bone fracture limits bone loss and reduces serious complications, including death.

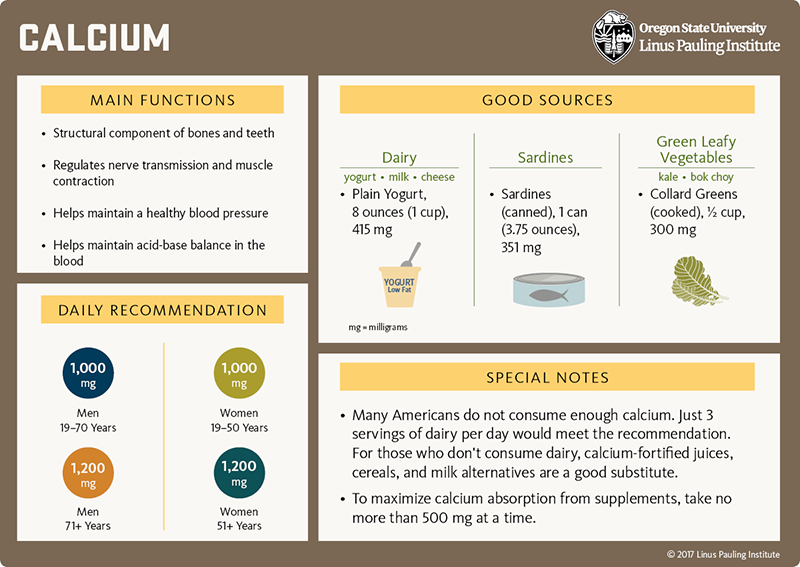

Calcium

What it does

General

- Calcium plays an essential role in cell-signaling pathways and is therefore fundamental to virtually all physiological functions.

Bone-specific

- Calcium is a major structural component of bones.

- Low calcium intakes may increase the risk of osteoporosis and fracture.

- The substitution of ultra-processed foods and soft drinks for unprocessed meals, milk, and other calcium-rich food is likely to damage bone health over the long run.

What we know

- Calcium supplementation is not effective to prevent postmenopausal and age-related bone loss; calcium can only limit bone loss in the first 1-2 years of supplementation.

- There is no consensus regarding calcium and vitamin D supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling older adults (see Table 3).

- The benefit of supplemental calcium (and vitamin D) on fracture risk might be restricted to people with known osteoporosis, those with low vitamin D status, and the institutionalized elderly.

- Calcium intake from food is preferred over supplements, and total intakes should not exceed 2,000 mg/day in adults >50 years.

| Foundation/Society/Task Force | Recommendations to Reduce the Burden of Fractures |

|---|---|

| [US] Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation |

|

| [US] American Geriatrics Society |

|

| US Preventive Services Task Force |

|

Highlight

Use the International Osteoporosis Foundation’s Calcium Calculator to find out whether you are getting enough calcium.

For references and more information:

- See the section on Calcium in the in-depth article on Bone Health.

- See the section on Osteoporosis in the Calcium article.

[Download PDF]

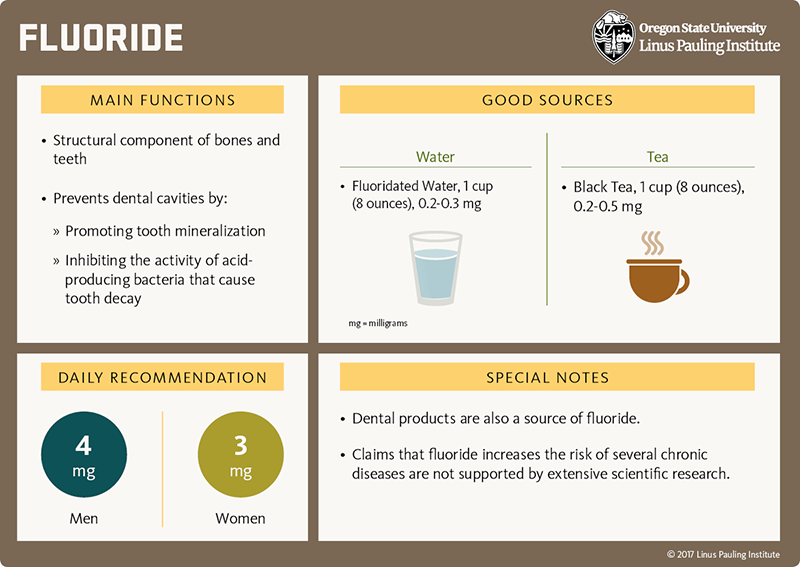

Fluoride

What it does

General

- Fluoride-containing dental products and adequate intakes of fluoride reduce the occurrence of caries throughout life by promoting tooth mineralization.

Bone-specific

- Fluoride increases the structural stability of bones through interacting with calcium phosphate salts.

What we know

- The level of exposure achieved through community water fluoridation (<3.4 mg/day) is unlikely to be helpful in the prevention of osteoporosis and fracture.

- Trials found that supplementation with daily doses ≤20 mg of fluoride reduced the risk of fracture.

- The US FDA does not currently approve the use of fluoride supplementation in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.

For references and more information, see the section on Fluoride in the in-depth article on Bone Health.

[Download PDF]

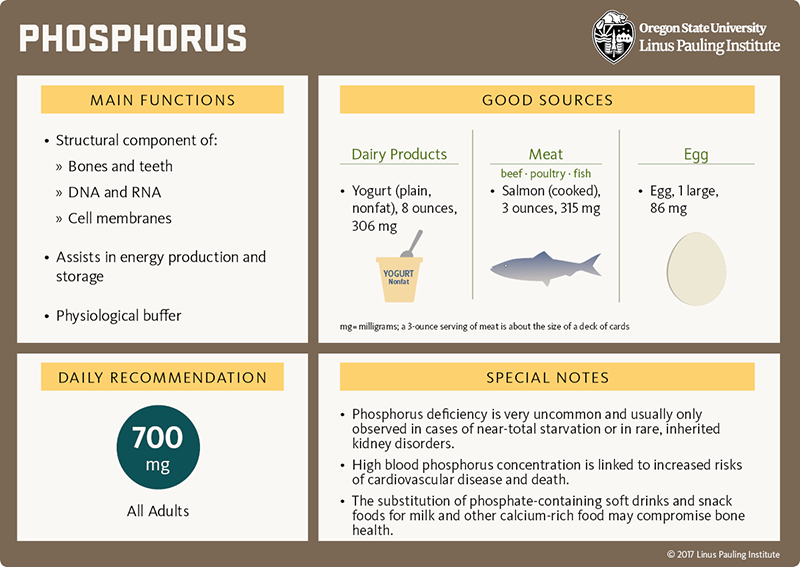

Phosphorus

What it does

General

- Phosphorus is an essential structural component of cell membranes and chromosomes and is involved in many biological processes, including bone mineralization.

Bone-specific

- Phosphorus and calcium form insoluble hydroxyapatite crystals that give bones their rigidity.

What we know

- Current intakes of phosphorus in the US population are well above the EAR (580 mg/day) and RDA (700 mg/day), with daily estimates of 1,602 mg/day in men and 1,128 mg/day in women. Yet, intakes of phosphorus currently experienced in the US have not been associated with a higher risk of osteoporosis.

For references and more information:

- See the section on Phosphorus in the in-depth article on Bone Health.

- Read the article on Phosphorus.

[Download PDF]

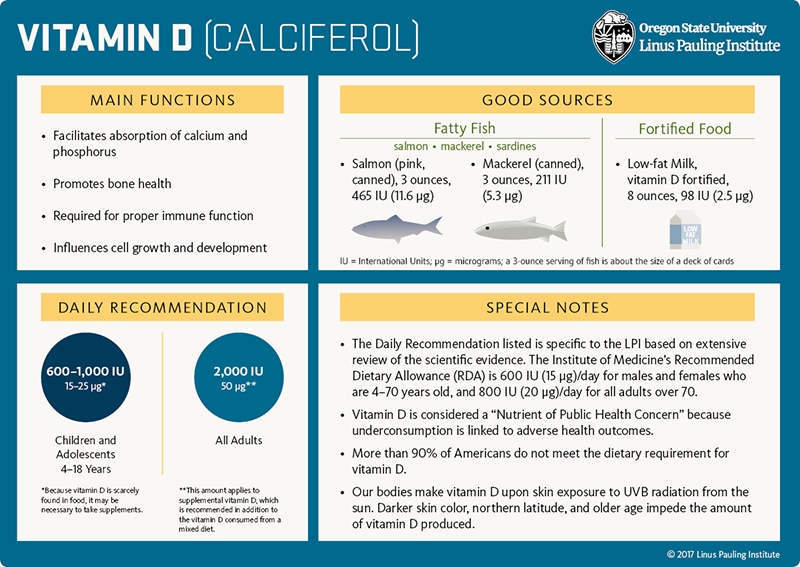

Vitamin D

What it does

General

- Vitamin D is made in the skin upon sunlight (UV) exposure and is also obtained from a few foods or from supplements.

Bone-specific

- When dietary calcium intakes are low, vitamin D stimulates the release of calcium from bone.

What we know

- Older people are at increased risks of poor vitamin D status (serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D values between 12-20 ng/mL) and skeletal disorders due to less sun exposure, a lower capacity for vitamin D synthesis, and reduced dairy intake.

- Current evidence suggests no effect of vitamin D supplementation alone on fracture risk.

- Vitamin D supplementation may contribute to reduce the risk of fall in adults ≥65 years.

For references and more information:

- See the section on Vitamin D in the in-depth article on Bone Health.

- See the section on Osteoporosis in the Vitamin D article.

- Read the US Preventive Services Task Force’s recommendations regarding Falls Prevention in Older Adults (See also Table 3).

[Download PDF]

Other Nutrients

- Excess sodium can be harmful to bone health in older women especially when they have suboptimal calcium intakes. Adopting a diet that increases potassium intake and reduces sodium intake (i.e., high in fruit, vegetables, and dairy, and low in meat) might help support bone health.

- Several additional micronutrients have essential roles in supporting and maintaining bone health (magnesium; vitamins A, B, C, and K). Yet, there is no evidence that supplementation at levels above current recommendations may be of benefit regarding the prevention of osteoporosis and fracture. Note that the US Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation advises against the use of vitamin K supplements in people at risk for blood clots and in those taking blood-thinning medications.

For references and more information:

- Find dietary reference intakes for all micronutrients that support bone health in the in-depth article on Bone Health.

- Read the in-depth article on Bone Health for a detailed discussion on the importance of micronutrients in bone health.

Alcoholic Beverages

- Light drinking may not be harmful to bone health. However, higher intakes of alcohol (≥4 drinks/day) increase the risk of fracture.

Physical Activity

- Regular physical activity, especially weight-bearing exercise, is associated with less age-related bone loss over time and with a lower risk of fracture.

- However, there is no evidence that even high-intensity exercises can limit bone loss due to menopause.

- Exercising may be detrimental to bone health if the body does not receive the nutrients it needs to remodel bone tissue in response to impact and tension forces generated by physical activity.

- Physical activity is highly beneficial across all stages of bone development. Even frail elderly people should remain as physically active as possible to preserve bone health.

For references and more information, see the section on Lifestyle factors in the in-depth article on Bone Health.

Smoking

- Smoking is associated with a higher risk of fracture and slower recovery from fracture.

- Smoking cessation reverses (at least partially) the increase in risk of fracture reported in smokers compared to non-smokers.

Definitions

Albumin – a major blood protein. It contributes to regulate blood volume (through “colloid osmotic pressure”) and transports various molecules (fatty acids, metals, ions, hormones, etc.) in the circulation.

Anorexia nervosa – a serious disorder in eating behavior characterized by self-imposed starvation causing severe malnutrition and excessive weight loss

Bone mineral density (BMD) – the quantity of mineral present per given area/volume of bone; a surrogate for bone strength

Bone mineralization – the process by which calcium and phosphorus are laid on the organic bone matrix

Bone resorption – the breaking down of bone by specialized cells (osteoclasts)

Caries – cavities or holes in the outer layer of a tooth — the enamel and dentin

Cell-signaling pathway – a cascade of events triggers by a signal outside a cell and resulting in a functional change inside the cell. Cell-signaling pathways play important roles in regulating numerous cellular functions in response to changes in a cell’s environment. Also refers to as cell-transduction pathways or signaling cascades.

Community water fluoridation – refers to the controlled addition of fluoride to water as a public health measure to decrease the incidence of dental caries

Cortical bone – the type of bone that makes up the outer shell of the skeleton

EAR – estimated average requirement. It is the nutrient intake value that is estimated to meet the requirement of 50% of the healthy people of a particular gender and age group in a population. It is also the best estimate of an individual’s requirement and thus may be used to assess the adequacy of an individual’s usual intake of the nutrient.

FDA – US Food and Drug Administration

Glucocorticoids – a type of steroid hormones, naturally produced by the adrenal glands (located on top of the kidneys). Long-term use may impair calcium absorption as well as bone formation, and precipitate osteoporosis.

Hydroxyapatite crystals – calcium phosphate salts forming crystals ((Ca)10(PO4)6(OH)2) that constitute the main mineral in teeth and bones

Low-albumin protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) – laboratory diagnosis of marginal PEM usually includes measures of serum albumin. However, albumin is not a specific indicator of PEM as its concentration in blood is altered in many conditions other than PEM.

Menopause – describes the period of a woman’s life when menstruation ceases

Osteoblasts – cells involved in making bone

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) – hormone secreted by the parathyroid glands

Primary prevention – refers to a range of activities undertaken to prevent or reduce the risk of an injury or disease before it occurs

RDA – recommended dietary allowance. It is the nutrient intake value that is estimated to meet the requirement of nearly all healthy people of a particular gender and age group in a population. It is a target value for an individual.

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D – a reliable measure of vitamin D status

Sex hormones – a type of steroids that are released by specific tissues – primarily adrenal glands, ovaries, and testes – and govern sexual development and reproduction; e.g., estrogen, testosterone

Tooth mineralization – the process by which calcium and phosphorus are deposited into dentin and enamel

Trabecular bone – the type of bone that fills the end of the limb bone and the vertebral bodies in the spine

Authors and Reviewers

Originally written in January 2018 by:

Barbara Delage, Ph.D.

Linus Pauling Institute

Oregon State University

Based on content reviewed in December 2017 by:

Connie M. Weaver, Ph.D.

Distinguished Professor and Department Head

Department of Nutrition Science

Purdue University

The writing of this content was supported by a grant from Pfizer Inc.

Copyright 2018-2025 Linus Pauling Institute

| Relevant External Links | Related Conditions |

|---|---|

|

|

Disclaimer

The Linus Pauling Institute’s Micronutrient Information Center provides scientific information on the health aspects of dietary factors and supplements, food, and beverages for the general public. The information is made available with the understanding that the author and publisher are not providing medical, psychological, or nutritional counseling services on this site. The information should not be used in place of a consultation with a competent health care or nutrition professional.

The information on dietary factors and supplements, food, and beverages contained on this website does not cover all possible uses, actions, precautions, side effects, and interactions. It is not intended as nutritional or medical advice for individual problems. Liability for individual actions or omissions based upon the contents of this site is expressly disclaimed.

You may not copy, modify, distribute, display, transmit, perform, publish or sell any of the copyrightable material on this website. You may hyperlink to this website but must include the following statement:

“This link leads to a website provided by the Linus Pauling Institute at Oregon State University. europebiolabs is not affiliated or endorsed by the Linus Pauling Institute or Oregon State University.”